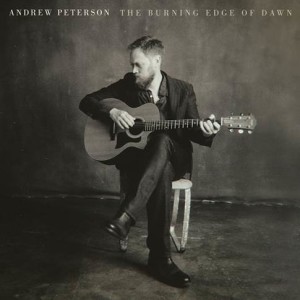

Don’t be fooled by the title. The dramatic imagery conjured by The Burning Edge of Dawn, the latest studio release from acclaimed singer-songwriter Andrew Peterson, is misleading, given the album’s style and substance are quite intimate. If anything, the album is a warm invitation into a personal season of change and grief for the Centricity Records artist. And if you’ve followed Andrew Peterson’s career, you’ll recognize it as par for the course.

Don’t be fooled by the title. The dramatic imagery conjured by The Burning Edge of Dawn, the latest studio release from acclaimed singer-songwriter Andrew Peterson, is misleading, given the album’s style and substance are quite intimate. If anything, the album is a warm invitation into a personal season of change and grief for the Centricity Records artist. And if you’ve followed Andrew Peterson’s career, you’ll recognize it as par for the course.

What’s atypical on this album is pretty much everything else. In the midst of myriad changes, Peterson changed his songwriting approach, his producer and his players. While the sessions for Burning Edge were intense, they were also very fruitful. Fortunately the one thing that hasn’t changed is Peterson’s ability to channel truth, authenticity and emotion in ways that cut to the core.

CCM: You’ve played with Gabe Scott over the years, but this is his first time producing your work. What led to that decision?

Andrew Peterson: It’s hard to say. Obviously he’s super-talented, and he’s come into his own as a producer. Besides that, though, I had a hunch that this record needed to feel different from anything I’d done before. Everything else was different: my two band mates weren’t touring with me anymore; my record contract was up, (though I decided to re-sign with them); I had finished The Wingfeather Saga; we were going to a different church. So it seemed strangely appropriate that I choose a different producer. Gabe is dear to me, one of my oldest friends and someone I’ve shared quite a bit of heavy stuff with over the years. If I was going to make a big change, Gabe was a safe bet.

CCM: Most albums document a season of time for the artist—the events and emotions playing out over certain months or years. What does Burning Edge say about the season you were in when writing it?

AP: When I listen to this record I hear mostly joy. Not necessarily in the lyrics, because there’s a lot of grief in there, but something about the way Gabe [Scott] produced the songs gives them a glow that balances out the shadows. The season was one of pretty significant shifts—like an earthquake hit and when the dust settled I couldn’t tell where I was. It was a season of depression, I guess. In some ways, there’s no better time to have to write a bunch of songs, because it forced me to think and pray hard about what was going on.

CCM: Did that decision lead to some surprising developments in the music that you made?

AP: I’ve never written songs this way before, and I think the fact that it pushed me out of a comfortable place made for better songs. We did a lot of deconstruction. Several of the songs went through several iterations before we landed what you hear on the record. There are musical and vocal moments—like in the song “Rejoice,” for example—that are wildly creative, and that’s all Gabe.

CCM: You’ve penned songs for various family members on several albums now, including a couple on this latest. Do you have a vision for writing those ahead of time? And is there a tension at all between being personal and accessible there?

CCM: You’ve penned songs for various family members on several albums now, including a couple on this latest. Do you have a vision for writing those ahead of time? And is there a tension at all between being personal and accessible there?

AP: No, I don’t really choose to write those songs ahead of time. Those tend to come from immediate and painful experiences in the family. That’s how it was with “Family Man,” and “Dancing in the Minefields” and “You’ll Find Your Way.” Those songs tend to come out faster because they’re quite literally my way of communicating what I want to say to those closest to me.

There’s no big artistic subtext or anything, no obscure metaphors. Those songs, like “We Will Survive” and “Be Kind to Yourself” are just plain English, me trying to tell my wife or my daughter something I need them to know. It’s counterintuitive, but the fact that the songs are specific and personal is what makes them accessible.

CCM: I’ve heard that sentiment from artists before—that the more specific or personal a song is, the more accessible it becomes. Have you found that across the years?

AP: Yeah, I think so. There’s this assumption that you have to broaden your focus if you really want to reach a lot of people, but there’s a long list of huge songs that are actually very specific and vulnerable. A few months back I was a part of an adoption fundraising concert my church put on, and they asked a bunch of songwriters to do cover songs. I chose “The Heart of the Matter” by Don Henley. Chances are, if you’re anywhere near my age or have ever listened to the radio, you have heard that song.

When I started learning the lyrics I was astonished by how vulnerable and confessional it was. I mean, I knew the song was deep, with a chorus like, “I’ve been trying to get down to the heart of the matter … and I think it’s about forgiveness … even if you don’t love me anymore.” But Henley lets us into his selfishness, his regret, the fact that he let work come between him and the one he loves. It’s what I love about Rich Mullins’ best songs.

On the other hand, writing from a sharp focus might limit the breadth of your reach when it comes to radio or whatever, but it also might deepen the reach into the heart of that one person who was really ambushed by the song. If I had to choose between reaching a ton of people with a shallow song, or reaching deep into the heart of just a few people with a song that’s about a very specific kind of heartache, there’s no doubt which I would choose. I’m one of those people whose life was literally changed because of a song.

When was the last time you were moved by music so personal?

AP: The most recent example I can think of is the title track to Cindy Morgan’s newest album, Bows and Arrows. Not only is it a masterful bit of songwriting, from a craft standpoint, but I superimposed my own story over it the first time I heard it. She wrote it for her daughter, who’s growing up fast, and when I heard it my mind was flooded with sadness and joy about all three of my own children, even though the pictures she painted were of her own story.

This might be a stretch, but I think the incarnation of Jesus is the prototype for what I’m talking about. Before the arrival of Jesus in Bethlehem, God was present, but intangible. In order to show us the depth of his love he put on flesh, gave himself a face that people could gaze at, arms to hug the little children, a mouth to kiss those he loved. God was no longer an idea, but someone whose robe we could touch.

So when I’m writing a song that may be about a big idea, a truth, or a question, I try to ask myself, “How can I incarnate this? How can this big though take on flesh?” And so, like Rich Mullins did with “Calling Out Your Name,” you don’t just write about faith that moves mountains—you write about the way a herd of buffalo literally shakes the earth in Kansas.

CCM: Speaking of personal, you took your son out as drummer on a recent tour. How was that for you—to be both, father and band mate?

AP: I can’t overstate the fact that making music with my family is one of the single greatest blessings in my entire life. It’s a dream come true. My son Asher has been playing for a few years now, and he’s really, really good. Not just technically good, but there are things about his personality—his careful attention to every situation he’s in, his humility, his self-discipline—that make him not just a good drummer or a good band mate, but a good man to have around.

The first few times we all played together as a family, I was both proud and super stressed. It was hard to balance being the bandleader and the father. But the kids are so talented and willing to listen, it was almost never an issue. By the end, I forgot they were there—which, believe it or not, is the highest compliment I can pay. A band that is so solid and tasteful that the singer doesn’t have to worry is a good, good band. I love it. I raised their allowance.

“I raised their allowance.” Haha! I love your music, Andrew. Love how you can go from deep to funny to everything in between, so effortlessly. Your album’s been in our car since it came out, and we love it. Have to watch my speed when that last song builds to the climax. God bless.